At the inaugural home game of the National Hockey League’s Seattle Kraken this October, team co-owner and private equity billionaire David Bonderman looked on as a tribute video showed footage of his undergraduate days at the University of Washington in the 1960s.

The Krakens lost the match, but it was nevertheless the culmination of years effort — and hundreds of millions of dollars — from Bonderman, 79. While setting up the hockey team, he was simultaneously working on a far bigger deal that had been decades in the making.

This autumn, investment bankers prepared documents to list shares in TPG — the buyout firm with $109bn of assets under management that Bonderman co-founded with his protégé Jim Coulter in 1992.

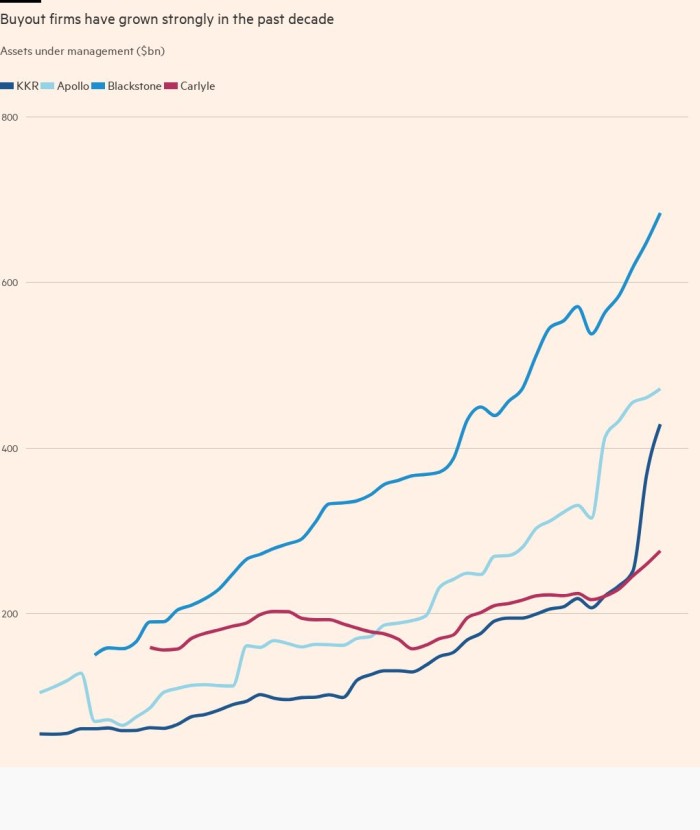

The long-anticipated initial public offering, unveiled in a securities filing on Thursday, means TPG will be following in the footsteps of Blackstone, Apollo, KKR and Carlyle, which helped shape the $4tn alternative assets industry in the 1990s and 2000s.

“[TPG is one ] of the pioneers of private equity, alongside firms like KKR and Blackstone,” says a veteran buyout billionaire who is close to both Bonderman and Coulter. “They’ve been visionaries in complex turnarounds and carve outs . . . making the firm permanent is a big legacy.”

The forthcoming IPO is poised to become the largest and most prominent in a wave of recent private equity listings, the scale of which has not been seen for at least a decade. It comes at a time of rapid growth in the alternative assets industry and soaring public market valuations.

It also sets the firm up for a future beyond Bonderman, whose success in the private equity industry could almost be described as an accident.

By the time he founded Texas-based TPG in 1992, Bonderman was nearly 50 years old and had already boasted an eclectic and accomplished professional life, which included a stint as a security guard working the night shift at Seattle’s iconic Space Needle monument.

As a litigator, Bonderman in 1983 defeated the Securities & Exchange Commission at the US Supreme Court in what would become a seminal case in insider trading law. He worked briefly as a civil rights lawyer in the Nixon Administration too.

His big break in business came in 1982 when the Texas oilman, Robert Bass, hired Bonderman to join his deals team after learning of his work on historic landmark preservation, including blocking the demolition of Manhattan’s Grand Central Terminal in 1978.

Bonderman and Coulter left Bass in 1992 to rescue Continental Airlines from bankruptcy, a deal that generated a return of nearly $700m on an investment of just $64m, according to securities filings.

It was that year they founded TPG, which quickly grew in stature by striking some of the industry’s biggest ever takeovers in the mid-2000s while raising over $34bn for two buyout funds just before the 2008 global financial crisis.

After the crisis, publicly traded rival Blackstone capitalised on the financial wreckage and became a colossus that now has a higher market valuation than Goldman Sachs.

But TPG was to remain private and more modest in its scope. It had been weighed down by several disastrous bets, most notably its buyouts of Texas utility TXU and casino empire Caesars Entertainment. Those deals, valued at more than $25bn each, ended up in bankruptcy court.

In 2008, the firm also financed a $1.35bn rescue of Washington Mutual bank, an investment that was wiped out within months. TPG would deploy more than $35bn of the cash it raised on the eve of the financial crisis, but both funds generated an annual return of less than 10 per cent, according to the firm’s IPO prospectus.

“TPG’s track record has lagged those of Apollo, Blackstone and KKR, especially during the crucial period between 2007 and 2012 when many of the large cap [buyout] firms went public,” said Gustavo Schwed, a finance professor at NYU and former private equity executive.

Today TPG’s assets under management are far smaller than the nearly $700bn that one time arch rival Blackstone now boasts. Still, it is well-regarded for its expertise in technology, healthcare and sustainable investments.

The firm, which counts San Francisco as its single biggest dealmaking hub, has recorded big investment wins in biotechnology, while also backing the likes of Airbnb, Spotify and Uber.

Now, as TPG prepares to be publicly traded, a new generation of insiders must try to close the gap with its larger rivals. It is coming to the stock market at a time when investors have shown huge enthusiasm for buyout firms, with Blackstone’s market capitalisation jumping by $70bn to hit nearly $150bn this year.

John Lerner, Harvard Business School professor, said there was “substantial scepticism” when Blackstone and others listed but that much of the “pessimism was unwarranted”.

“I would not be surprised to see an increase [in the] popularity of ‘public private equity’ . . . in the years to come,” Lerner added.

The foundation for TPG’s public offering was laid during the financial crisis, when it recognised that it was its investments in growth-orientated companies that were driving its returns.

At the time, Coulter, nearly two decades younger than Bonderman, oversaw TPG’s daily operations from San Francisco, helping reposition the firm to focus on growth while relying on a group of specialist dealmakers that have since risen to prominent roles within the company.

By 2014, Bonderman was chair of the firm and Coulter was its CEO, and they started to do the groundwork for a public listing. The following year, they hired former Goldman executive Jon Winkelried as a co-chief executive, allowing Coulter to become less involved in day-to-day management.

When he was hired, Winkelried was handed equity awards, which have now fully vested. The arrangement was described as the “Winkelried Pre-IPO agreement” in the securities filing this week and reveals that the firm has been planning to go public for at least seven years.

With Winkelried helping to oversee daily operations, TPG began to raise new capital, including a $10bn buyout fund in 2015. A string of other funds were dedicated to investments in fast growing markets in Asia.

Performance recovered, led by a collection of TPG’s sustainability-focused impact funds known as the Rise platform, now overseen by Coulter after its co-founder Bill McGlashan pleaded guilty in a nationwide college admissions cheating scandal.

TPG Rise now has $13bn of assets after raising a $6bn climate fund earlier this year and has generated annualised net returns of 20 per cent, according to the IPO documents.

TPG’s expanding platform of growth equity, real estate and Asian investments also performed strongly, though they are not characterised as standout performers by industry insiders. TPG states in its prospectus that since its founding it has achieved an annualised gross internal rate of return of 23 per cent in buyout investing.

However, that calculation includes the enormous profits from the 1993 investment in Continental Airlines, a deal executed before the formal creation of TPG.

In May this year, TPG named Winkelried as sole CEO and Coulter as executive chair, then months later promoted a handful of longtime partners Some junior dealmakers have also been elevated to the inner circle.

Like its peers, TPG pays its executives handsomely, with Bonderman and Coulter each receiving at least $160m of cash distributions in 2020 and 2021 combined. Winkelried received $76m in the same timeframe.

TPG declined to comment for this article.

The firm plans to shift from a partnership structure to an ordinary corporation within five years, which would allow it to join stock market indices.

It is unclear whether it will trade at a multiple similar to Blackstone, Apollo and KKR, which have diversified away from the erratic if large incentive fees generated by leveraged buyouts.

Investors have assigned TPG’s larger rivals with high valuation multiples because they have shifted towards steadier credit and real estate investing, something that Bonderman’s firm has not done at scale.

The private equity billionaire said that TPG had done “a great job pivoting away from the early . . . successes that drove performance in the firm’s first decade,” but noted the business did not benefit from the credit or insurance assets that investors are attracted to. “It’s very different from a Blackstone or Apollo.”

Two months have passed since Bonderman, a soon-to-be-octogenarian, was lauded at his hockey team’s first home game. Now he will get to look on again as his company makes its Wall Street debut.

Additional reporting with Kaye Wiggins in London

Credit: Source link